SOLID Principles For Game Developers

The SOLID principles are a set of 5 software development principles coined by “Uncle Bob” (Robert C. Martin). They are a set of guidelines for Object Oriented Design (OOD), specifically for class design. They are widely used by agile business programmers however they are generally unknown amongst game developers. This article describes the principles and frames them in common game development situations.

The SOLID principles are a set of 5 software development principles coined by “Uncle Bob” (Robert C. Martin). They are a set of guidelines for Object Oriented Design (OOD), specifically for class design. They are widely used by agile business programmers however they are generally unknown amongst game developers. This article describes the principles and frames them in common game development situations.

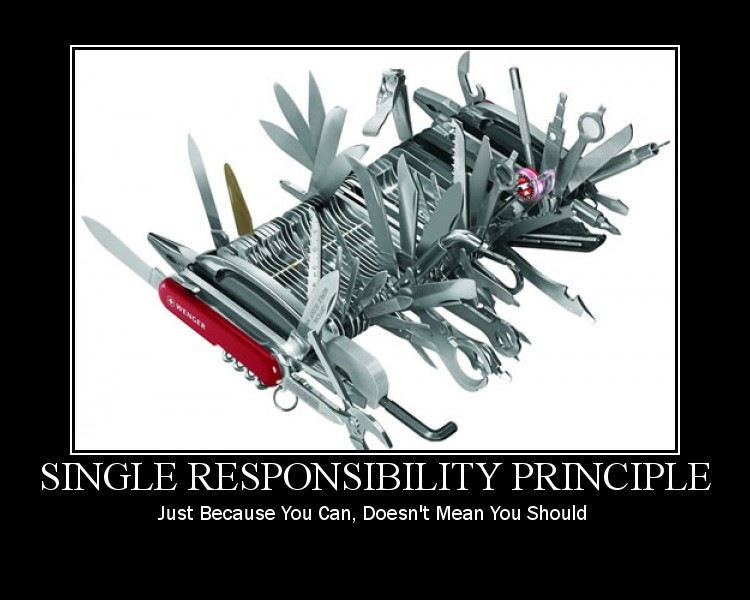

Single Responsibility Principle

“There should never be more than one reason for a class to change.”

The first principle is the cornerstone of the set and gives the greatest return on investment when followed correctly. It states that each class should have only a single responsibility and therefore reason to change. Keeping each class small and tightly focussed allows developers to know exactly where to go to find or add particular functionality to the game.

Why is having more than one responsibility bad? Multiple responsibilities means there is coupling between separate pieces of code. Changes to one responsibility reduce the ability for the class to meet the requirements of the other responsibilities. This leads to fragile design that breaks often and in unexpected ways. “Why did changing from rendering API break jumping in the game?”

The way to fix code that breaks this principle is to separate each responsibility into its own class. The first step can be to extract an interface per responsibility. Other classes can then rely on these interfaces rather than the class itself. The class can then safely be split up into separate classes for each responsibility that each implements a single interface.

When have you got it? – The usual culprit breaking this principle is that one (or group) class that’s hundreds or thousands of lines long. You know the one I’m talking about. Often it’s the GameObject or Entity class that everyone seems to throw code into. This class usually has about 500 reasons to change, and therefore 500 responsibilities. It’s usually involved in the heinous bugs that crop up constantly.

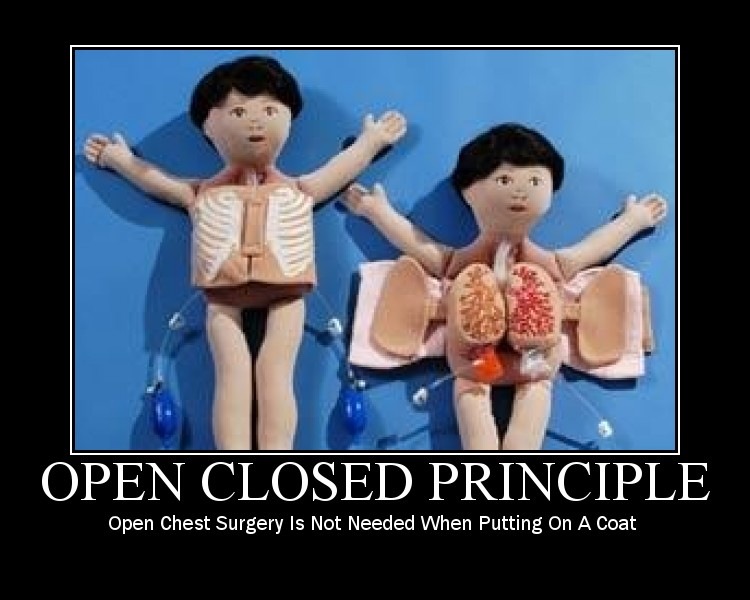

Open Closed Principle

“Software entities (classes, modules, functions, etc.) should be open for extension, but closed for modification.”

The goal of this principle is for each class to change as infrequently as possible while allowing it to be used in as many situations as possible. While these two requirements may seem at odds they actually complement each other to generate robust design. A class is open for extension means that the behaviour of a class can be changed in new and different ways as the requirements change. A class is closed for modification when no source code changes are required for these changes in requirements to be met.

This principle can easily be resolved with data driven design. By passing the required configuration data to a class it can easily be extended reducing its need for modification. Any variables (in the mathematical sense) should be passed to the class so that the classes definition itself (the code) does not specify the functionality of the class alone. I find this the easiest to think about in terms of the basic OOD principle of data and operations. The class defines the operations it can perform (its functions) and the data that it operates on. As much of this data as possible should be passed to the class/function. This moves the configuration of its data outside the class itself to the calling code increasing its ability to change.

When have you got it? – This is the file you dread checking-in because everyone seems to be working on it all the time. No matter what system you’re working on, these files always seem to be involved.

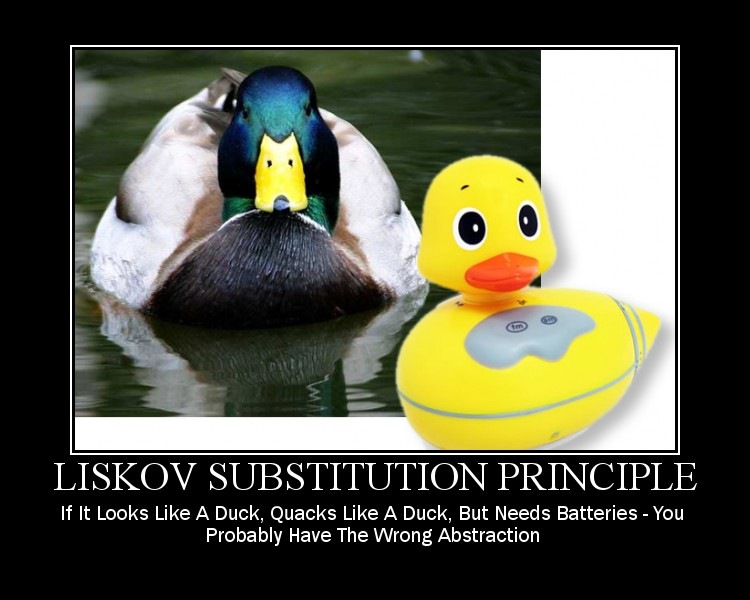

Liskov Substitution Principle

“Functions that use pointers or references to base classes must be able to use objects of derived classes without knowing it.”

Inheritance and polymorphism are powerful mechanisms for solving complex problems with simple solutions. They are also powerful mechanisms for creating bugs and problematic code. This principle involves making sure inheritance hierarchies are sound and not being abused by code that introduces bugs that are hard to find. While it seems simple on the surface, this principle can be quite complex to solve correctly.

The first steps to solving this problem are to find instances of checking for an objects type – both its own and that of objects it’s working on. Beyond this easy first step comes a principle known as “Design By Contract”. Each function has a set of conditions that must be true before it is called (pre-conditions) and a set of conditions it guarantees are met after its completion (post-conditions). These are often implied conditions kept in the mind(s) of the programmer(s) working on them. The first step is formalising these conditions into code. Once this step is completed the following rule can be met – “Derived classes can only weaken pre-conditions and strengthen post-conditions”. Put another way, functions of a derived class should expect no more than their base class and promise no less. This principle is important because of the fact a model viewed in isolation cannot be meaningfully validated. You don’t know whether your new “Tank” class is valid until you run it in the context of its parent, siblings and other game system.

When have you got it? – Classes breaking this rule are really easy to find. Look for any base class that uses run-time type information (RTTI) to interrogate its own type (or the type of an object it’s working on). As soon as the GameEntity class is checking if it’s of type “Tank” to do some special code, you’ve broken this principle. The class should be able to polymorphically call functions without caring about the actual type of the object.

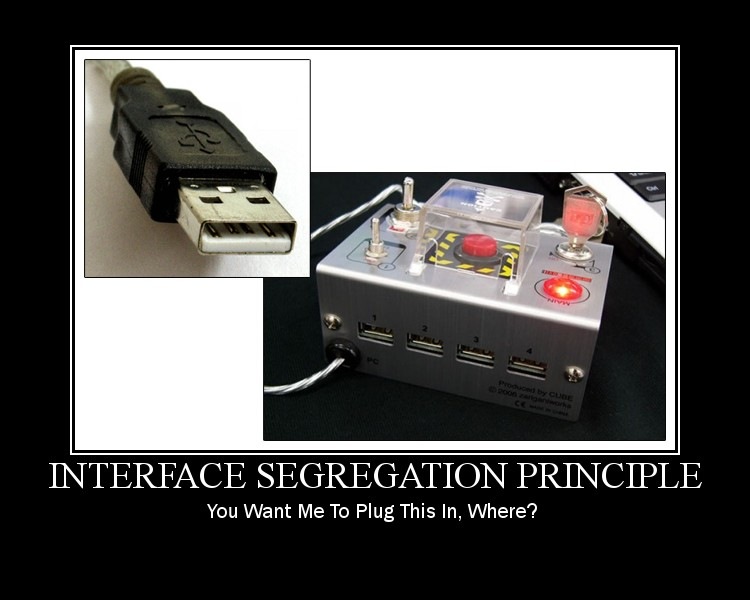

Interface Segregation Principle

“Clients should not be forced to depend upon interfaces that they do not use.”

Interfaces should be used for communication between different objects to encourage clean, modular code. This principle takes that concept further by making sure that the interfaces we use are themselves clean and unified. The larger the interface, the more the client is relying on functionality of another object. By keeping small segregated interfaces each object will rely upon only the smallest set of functionality it actually requires. This reduces the complexity of links between objects and more importantly, lets someone reading your code know exactly what each class relies upon. Rather than one “fat” interface we break the interface up into multiple smaller groups of functionality that each serve a different client.

This principle links back to the single responsibility principle nicely. In this case each interface should have a single responsibility. This lets you explicitly state the functionality requirements of each object based on the interfaces it requires.

When have you got it? – Look at all your interfaces (abstract classes) and make sure their listing of functions are homogenous. An easy way to tell you’ve broken this principle is when there are small groupings of functions within the interface definition. Whitespace is the key here, the more whitespace between the groups of functions, the more disparate they are.

Dependency Inversion Principle

“High level modules should not depend upon low level modules. Both should depend upon abstractions.”

“Abstractions should not depend upon details. Details should depend upon abstractions.”

This is a key point that I had not heard of at all in game development until recently. This principle is quite the opposite of how many developers are used to working. Usually, if a class depends on another class, the client will instantiate an object of that class and then act upon it. Dependency Inversion (also called Inversion of Control) turns this on its head. Instead of the client being responsible for creating the object, it is given the object it depends on. This takes the control away from the client and moves it to the owner of the client, often the game engine.

A good example of this is in a rendering system. Rather than instantiating a rendering object, or directly calling the classes of the rendering API, the rendering system should receive an interface to the low level rendering functionality. By relying on an interface that is given to the rendering system, the low level rendering API can be changed without making breaking changes to the client rendering system. It becomes obvious if breaking changes occur as the low level rendering API’s interface will require changing.

When have you got it? – When two systems are talking to each other, how do they do it? If they are using concrete classes then look for opportunities for them to rely on interfaces instead. The best way is for the class to take as parameter to its constructor an interface reference to the class it needs to work on. This also makes it obvious what sub-systems are particular class is reliant on.

Conclusion

What are your thoughts on the SOLID principles? Do you see benefit from adopting these in the games industry as web and application development has done?

SOLID Motivational Posters, by Derick Bailey

I build software. The best place to find me is on

I build software. The best place to find me is on